The first real memories of my father are from when I was around three and a half years old. I vaguely remember the excitement of going to the small aerodrome in Daman (then still a Portuguese colony on the Gujarat coast). Though it was a weekday my mother dressed both my elder brother and me in our Sunday best. She looked prettier than usual and smelled very nice.

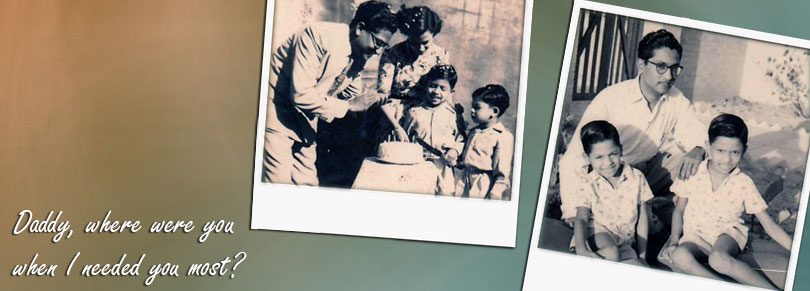

Then her father came and took us to the aerodrome, where we would sometimes go to see a planeland or take off. But that day was to be extra-special—we were going to receive and meet our father for the first time since we were babies. Up until then I had only seen photographs of my father which were all over his family home, where we lived with my grandmother—photos of him as a young boy with his family, as the handsome young groom in the wedding album (where I looked in vain for my brother and me), then holding my brother or me as babies, and most recently photos alone or with friends in a strange place where he was working and coming from, on a visit home.

The month that followed is a photomontage of memories—my mother and father sitting and talking while my brother and I played nearby with the toys he had brought us; my dad taking my brother and me on evening walks to the Damanganga river and actually taking us half way across the broken bridge to get a view of the ferries crossing, fishing boats returning with their catch, the setting sun, and giving us Wrigley’s gum to chew on while he told us stories. All too soon the month flew by and we went again to the aerodrome; this time to see daddy (Papai) off, back to where he had come from, somewhere “near Egypt” as he told us.

After that I remember missing my dad-of-the-special-month as I had never missed the dad-in-the-photo-frames and albums. My dad had become very real to me and I wanted to be with him again. We knew from his letters read out by my teary mum that he too missed us very much and was longing to see us again.

We soon went to join my dad in the Gulf for a year. It would take a booklet to record my memories of the one year of our family together in our new home, seeing my dad every day. So, a year later, when only my elder brother and I were once again dressed up to fly with UM (Unaccompanied Minor) tags, the parting was even more difficult.

I was six and a half and I understood much better this time what leaving both my mum and dad meant. We were told it was for our best—for us to go to Bombay to start ‘English school’ and for my parents to stay there so that my dad could earn enough to look after all of us. The only saving grace was that we were to live with a childless uncle and aunt, who looked after us for the next six years. We did see our parents and younger brother every year but the rest of the time we were only connected through letters and the occasional photograph.

After a year in boarding school, my mum with my two younger brothers came to Bombay and we lived together as a family—minus my dad, who joined us a couple of years later. By then I was a teenager starting high school. Though my dad and I had much in common—reading, debating issues, and music—the years apart had resulted in some emotional distance.

We were never really close. When I look back, I wonder whether it was because of him or me. Then I discovered that my grandfather (who was knighted for his services in the Gulf) had also shipped his eldest son, my dad, and then the two younger sons to boarding school in Bombay. I never got to explore what that felt like to him; he certainly never wanted to talk about it.

Eventually, I married and emigrated. There I landed the best job I could get, literally as a “high flying” management consultant, involving travel—most of the year. Both my sons were born during those years. Besides the short vacation time and the occasional project in town I was travelling the length and breadth of North America from Sunday night through Friday night.

I became a weekend dad to my sons. I descended on Friday nights carrying “manna” from the heavens—cheese and crackers from the plane—which my older son looked forward to with great anticipation. Trying to be the best husband and father in just a weekend strains any definition of “quality time.”

Eventually it contributed to the breakdown of my marriage, the most painful part of which was to see my sons disappear with their mother through airport security, headed to their new home “near Egypt.”

Turning Point

A couple of years before that happened I had come to a personal relationship with God. I began to learn the importance of a father being close and accessible to his children. I made attempts to change my job if not my career but I was not able to change that in time to avoid the painful consequences it brought on our family. I can only say that it is by the grace of God that when my young adult sons and I were reunited after a gap of a few years, we were able to once again have a loving relationship.

I know that if I had to live my life over, I would make family the next priority, immediately after God. I was to discover this is easier said than done. In the case of my father’s side of the family this “curse” of absentee fathers had come down three generations but has now been broken. I do not use the word “curse” lightly for as studies by psychologists and sociologists have proven, across cultures the “absentee father” factor is a significant contributor to both psychological and behavioural dysfunction as well as to sociopathic, even criminal behaviour.

MIA fathers

Since my return to India, I have become increasingly aware of the phenomenon of MIA (Missing In Action) fathers in families that are still whole. I do not know of any study done on the subject but I would hazard a guess that a significant percentage of Indian children have absentee fathers. Let’s begin from the (socio-economic) bottom up: so many of the men serving in our cities as labourers, construction workers, drivers, etc. leave their families behind in their “gaon” to earn, save and send the maximum home.

Even in the middleclass, some jobs require significant time away from home. One of the worst case scenarios is that of the “shipee” father who sails in the merchant navy for several months before coming on ‘shore leave’ for a couple of months and then off again. In the case of the armed forces, only officers can have their families living with them and that too at a base, not on the front.

Then again, to avoid constant transfers from state to state, some parents prefer to put their children in boarding schools. Boarding schools, even the very best, are no substitute for, let alone improvement upon, kids growing up with both parents. Even today, people who serve in difficult and remote areas put their children in boarding schools “for their own good.” Few if any parents have done a cost-benefit analysis of this option before dispatching their children there, often at great cost and sacrifice.

I am not suggesting that the physical presence of a father is a sufficient factor for a healthy family, but it is definitely a necessary one. As Woody Allen quipped, “Eighty percent of life is just showing up.” It is only then that we can begin to talk about quality time, emotional connectedness, role-modelling, and so on. Like in many of India’s government schools, the students are present and eager to engage and learn but all too often, the teacher is absent.

As a father who has learned the hard and painful way, I appeal to fellow-fathers—let’s be present to our children, engage emotionally, teach and continue to learn. The Old Testament in the Bible ends with a choice—God’s blessing consists in the hearts of the fathers turning towards their children, and vice versa; if not, we are cursed. Fathers, what will you choose this day—a blessing or a curse?

Leave a Comment